One of the key concerns for advertisers and app developers wanting to dip their toes into Apple Search Ads is scaling their reach and making the most out of the high-intent audiences who are active on the app store. The idea behind a discovery campaign is just that: to facilitate mining of new keywords that are relevant to the app. But how well does it actually cater to the promise? Is it really worth the investment?

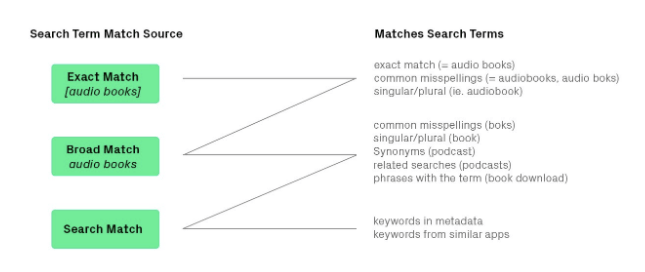

We employ discovery campaigns for all our clients as they are pivotal to reaching out to more users who could possibly generate positive results in terms of performance, keyword discovery, and volume (scale). To facilitate this, we use search and broad match in such campaigns. With Search Match enabled in ad group settings, ads are matched to relevant search terms that we are currently not targeting or might have missed in our keyword research. Of the several sources the algorithm uses to match the ads to relevant search terms, the metadata from your app store listing, information about similar apps, category-related keywords, and other search terms that lead to downloads for other apps in that category, are the most important. By providing broad match keywords, the algorithm looks for related searches and phrases that include that term, which can be very broad. For instance, the broad match keyword ‘audio books’ would not only match with ‘audiobooks’ or ‘audio boks’ but also ‘book’, ‘podcasts’, ‘book download’, etc. We have encountered unrelated matches on several occasions for our clients and have been forced to pause such broad match keywords. See below a visual representation of how ‘exact match’, ‘broad match’ and ‘search match’ will search for new terms.

However, discovery campaigns, in our experience, must not be given free rein, as the cost per acquisition (i.e. CPA, or cost per download) can very easily get out of our hands and might not provide the value that we are looking for. It is, therefore, important to set low cost per tap (CPT) bids and gather enough data. If we want an additional layer of control, we can add CPA goals at a later stage. Once we have a handle on the performance, we can bid higher and ease up the CPA goals. We dealt with the structure of a discovery campaign and how it should be set up, here. There is more information on how to leverage the keyword layer for scale and performance in the ASA Stack, developed by Andrea Raggi, here.

In this article, we will look at discovery campaigns from two different perspectives: performance and, of course, keyword discovery.

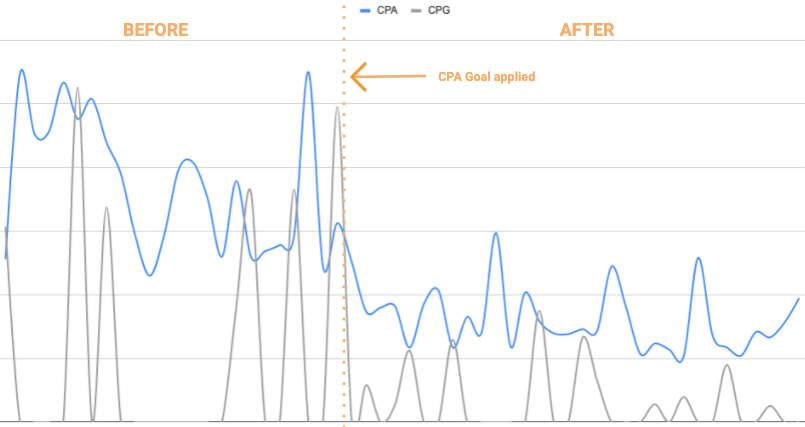

While their core purpose is to uncover some interesting opportunities for us, discovery campaigns can sometimes boost the overall performance if carefully monitored (keeping the bids at a minimum and adding CPA Goals). This could mean getting the best of both worlds, but it is also a thin line that if not trodden carefully, could lead to poor performance. As we continue, we will look at the impact achieved upon adding a CPA Goal to a discovery campaign. The analysis was made over a 90-day period.

Before:

The campaign started off with a high cost per download (CPA), and as result, a high cost per action/goal (CPG) that was beyond our target. Despite the additional scale that this campaign was driving, its utility had to be reconsidered given the high costs. After observing this trend for a couple of weeks, we added a CPA goal that would ideally lead us to achieve our target CPG.

After:

Upon adding the CPA goal to the campaign, we noticed that the CPA and CPG dropped by about 47% and 64% respectively.

Being able to exercise a certain level of control over the cost while getting additional volume turned lucrative for these campaigns. As a rule, we have been making sure the CPA goals are in place whenever we work with discovery campaigns as a part of our strategy, as this approach usually tends to deliver satisfying results.

What about the overall performance of discovery campaigns across different metrics, you ask? The answer to that question may not be as straightforward as you would expect. Reflecting on the performance that we have achieved with clients so far, we have seen that a lot depends on the initial investment, market conditions, the category of the app, the competitive landscape, and possibly even the metadata. There are clients that run into high CPGs and do not invest further in discovery campaigns, and hence the overall conversion volume turns out to be low. And since we are not tracking revenue for all the clients and the target event we optimize for varies, it is hard to notice a general trend of how discovery campaigns perform when it comes to conversion volume and return on ad spend (ROAS). Some clients see an incredible uplift in conversion volume, with the number of goals coming from discovery campaigns contributing up to 60% of the total volume. And as counterintuitive as it may sound, this could be because of relatively high CPA goals, which help in acquiring more valuable traffic in the case of some apps. There are other clients where discovery campaigns contribute as little as 2% of the goal volume but end up with a ROAS of around 79%. We plan to delve deeper into this interesting finding in a follow-up article soon.

A couple of other questions pertaining to keyword discovery might arise when we talk about discovery campaigns. Some of the questions that we seek to answer through this article are:

- How are the discovered search terms dealt with?

- What is the volume and frequency of the search terms that are ‘discovered’?

- What is the percentage of the volume over time that we receive on visible search terms vs. hidden, low-volume search terms?

- How do they end up performing when added to other campaigns (namely probing), and are those good-quality search terms?

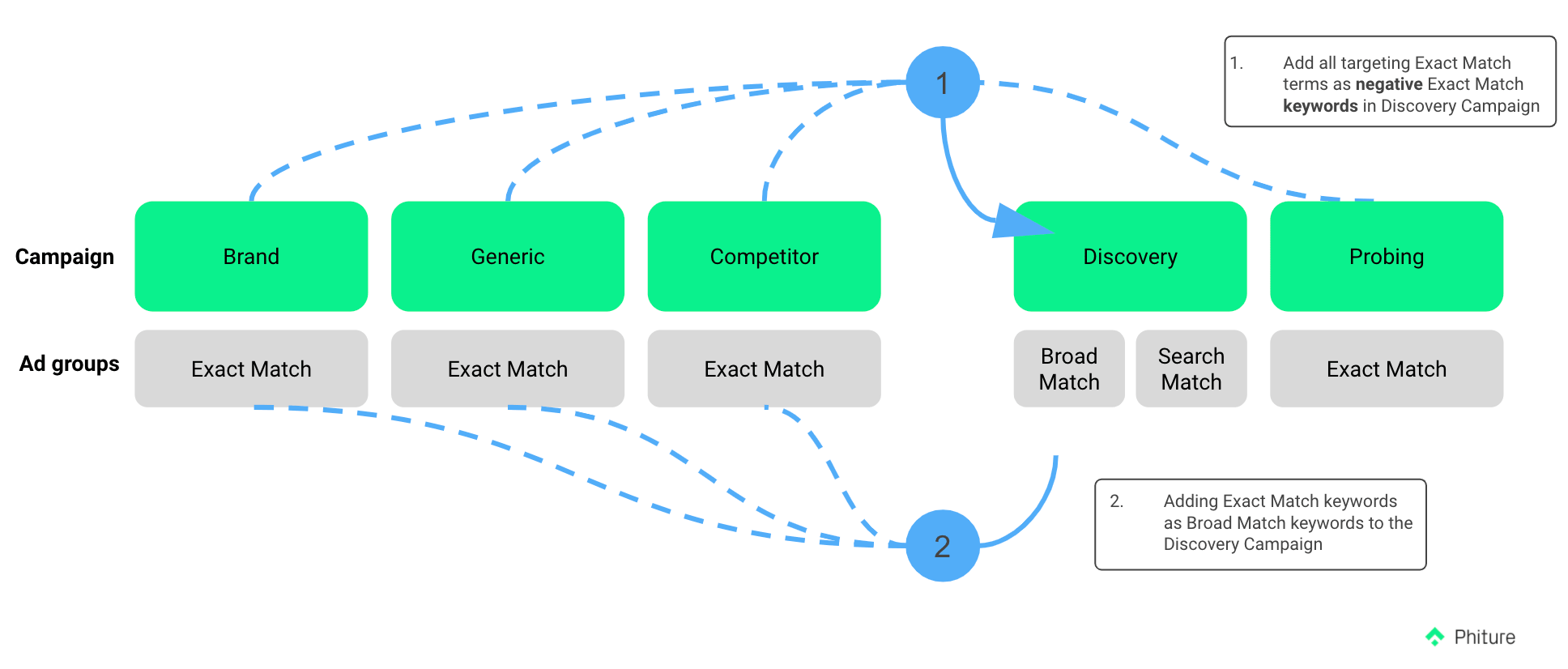

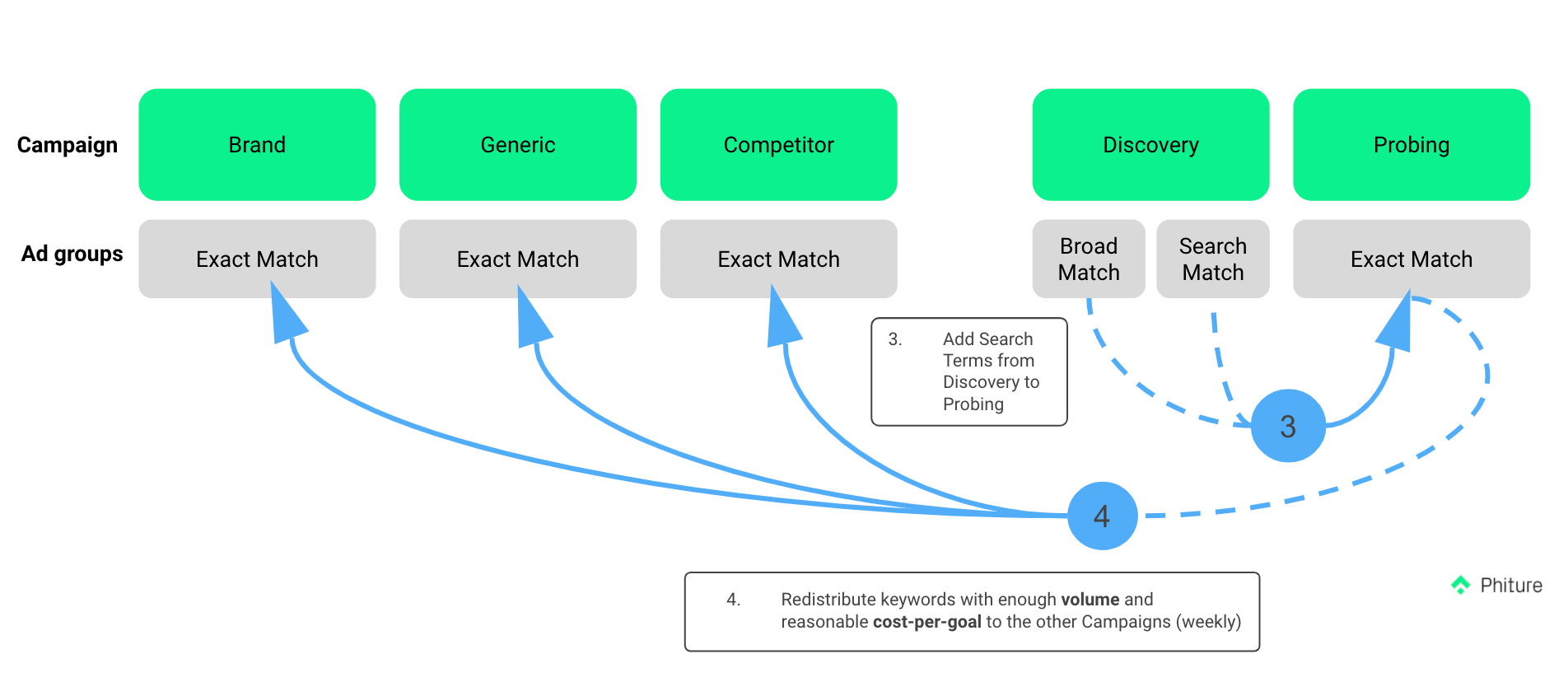

Let’s talk about how we work with discovery campaigns and the ‘discovered’ search terms. At Phiture, we employ scripts to help us automate some aspects of campaign management. This involves adding found search terms as negative, exact-match keywords to our discovery campaign, so that we do not end up matching with similar search terms. And, also, adding those ‘discovered’ search terms as exact-match keywords to a probing campaign, which the script does on an hourly basis. The idea of a probing campaign is to get conversion data (post-install data from a Mobile Measurement Partner) for those newly discovered keywords and ascertain their potential.

We have the option of working with both ‘broad match’ and ‘search match’ match types in our discovery campaign. The script goes even further, in that it also adds those exact-match keywords as ‘broad match’ in the discovery campaign, so that we end up with ‘broad match’ and ‘search match’ ad groups. The intention here is to uncover as many possibilities as we can. Finally, the probing keywords that seem to have a lot of potential are redistributed to the respective core campaigns.

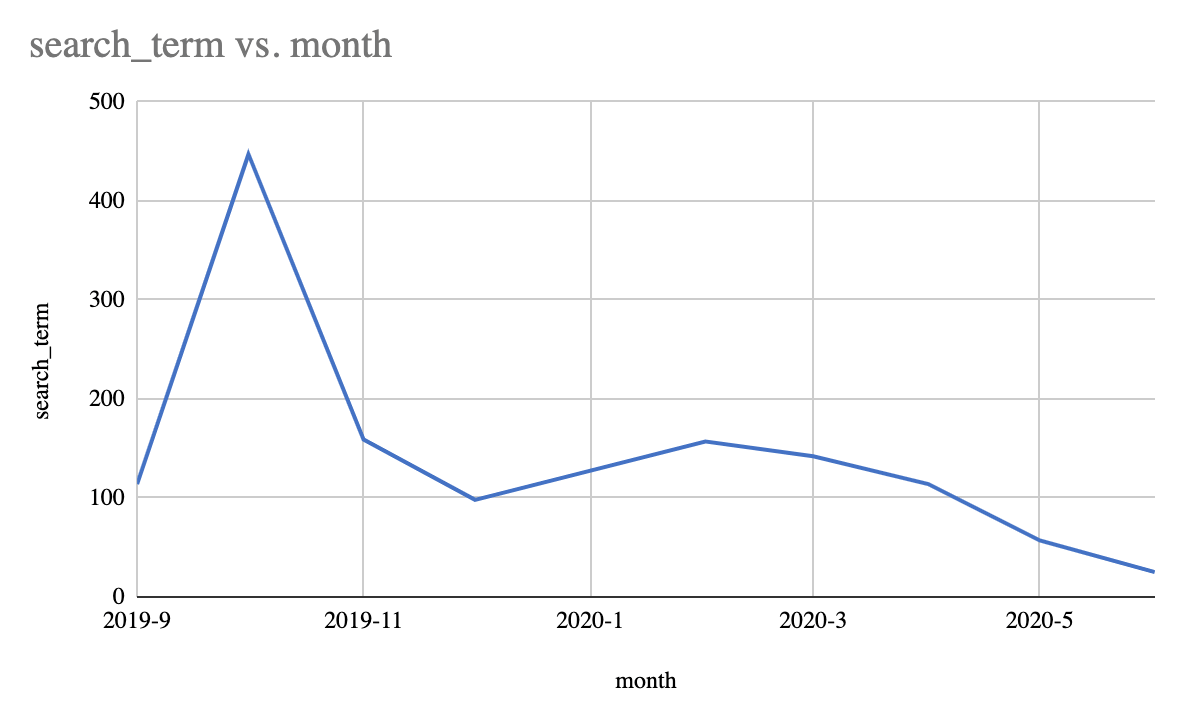

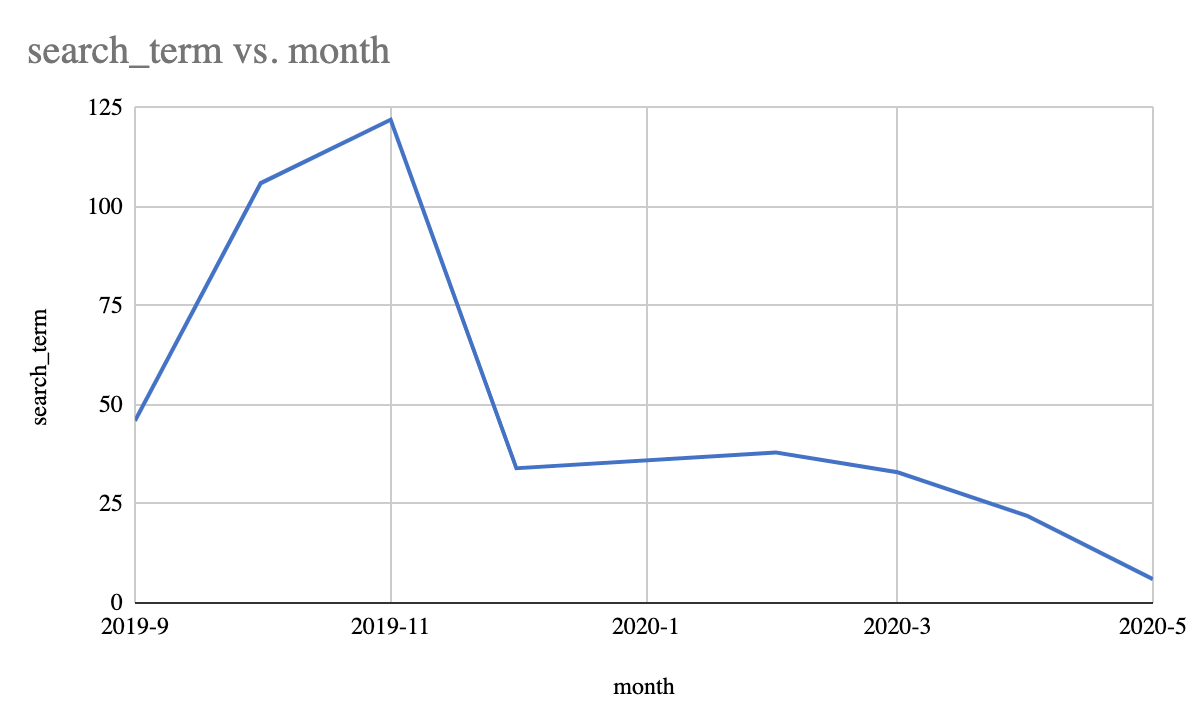

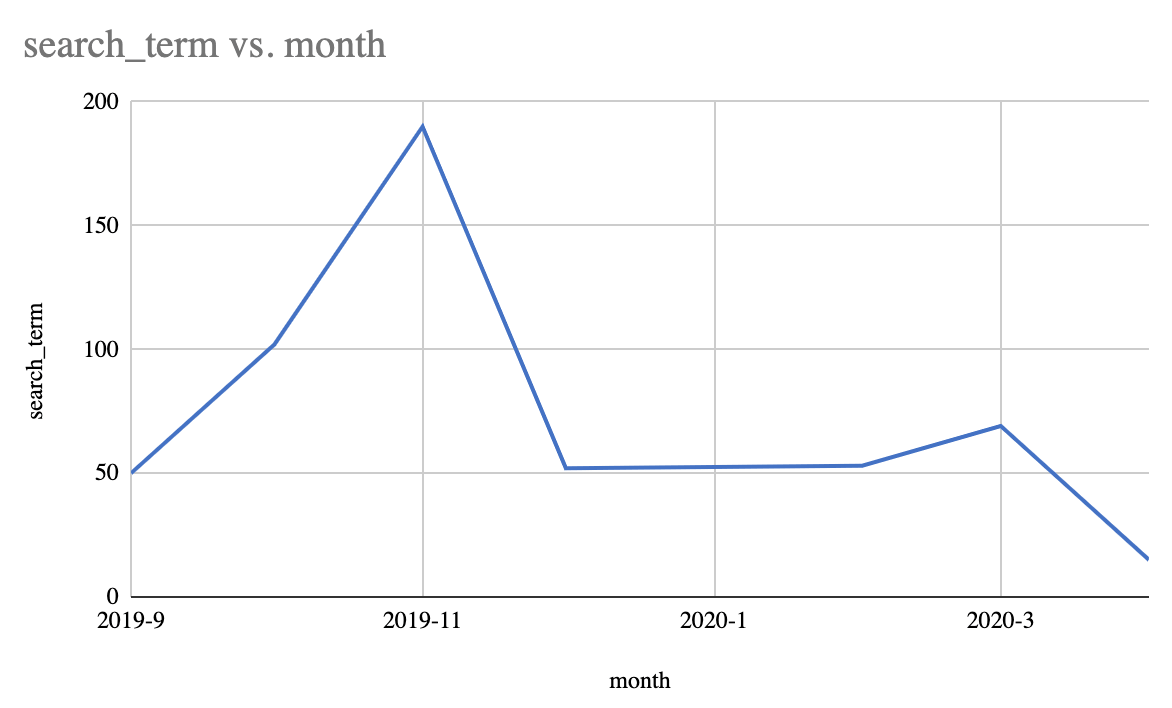

Now, going back to the question of how many search terms are actually discovered in the process, we looked at the distinct search term volume generated through ‘search match’, month after month, per client. The volume of search terms in absolute terms definitely varies, but the pattern below stood out. It is to be noted here that no additional checks or controls were added to the campaign during this period except the CPA goals that were already in place.

Let’s look at some examples here from different clients across various storefronts.

We can notice here that, after an initial surge in the volume of discovered search terms that lasted for roughly two months, the volume eventually plateaued. At this point, we have exhausted all the different possibilities –– or so it seems.

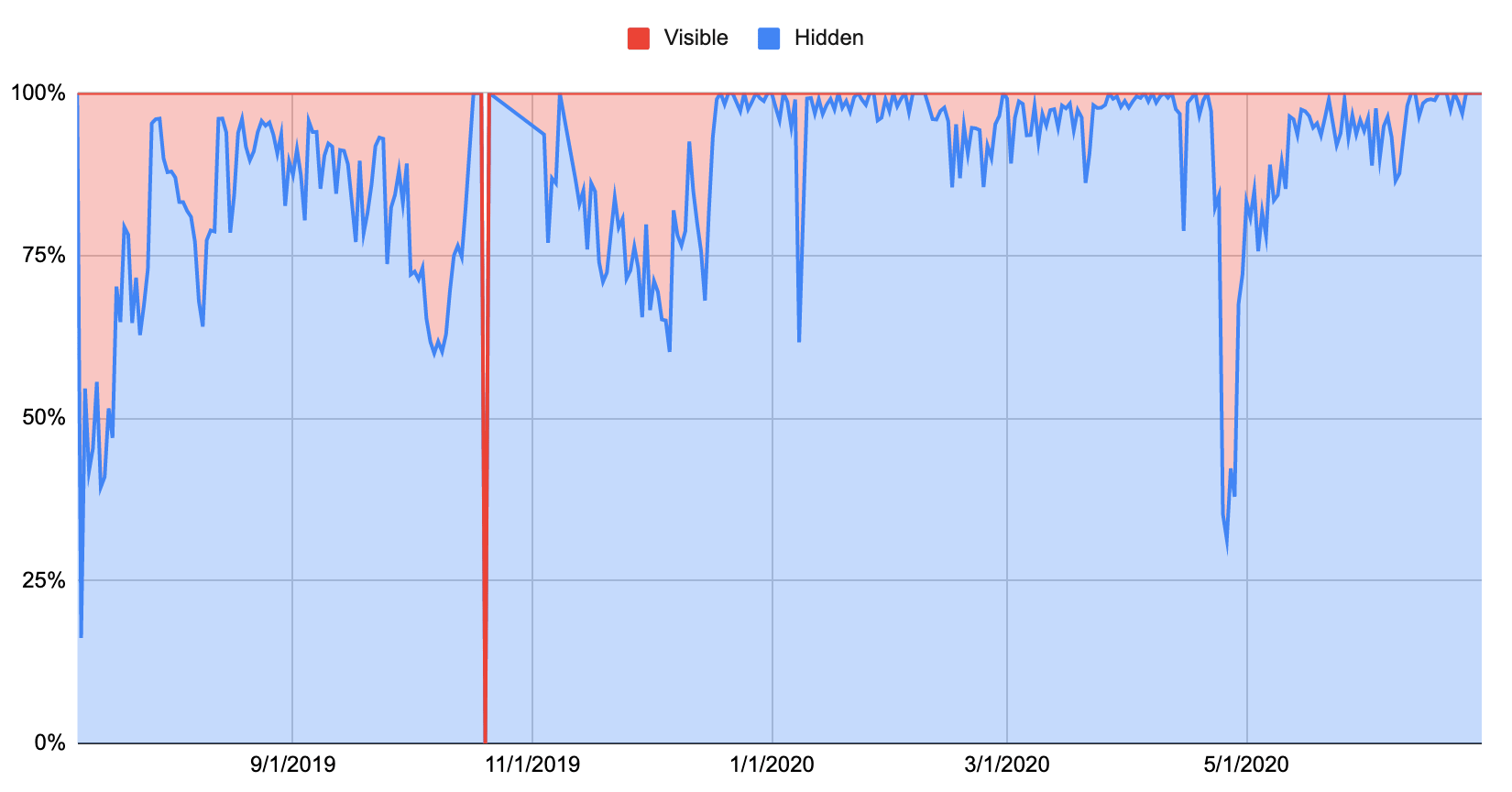

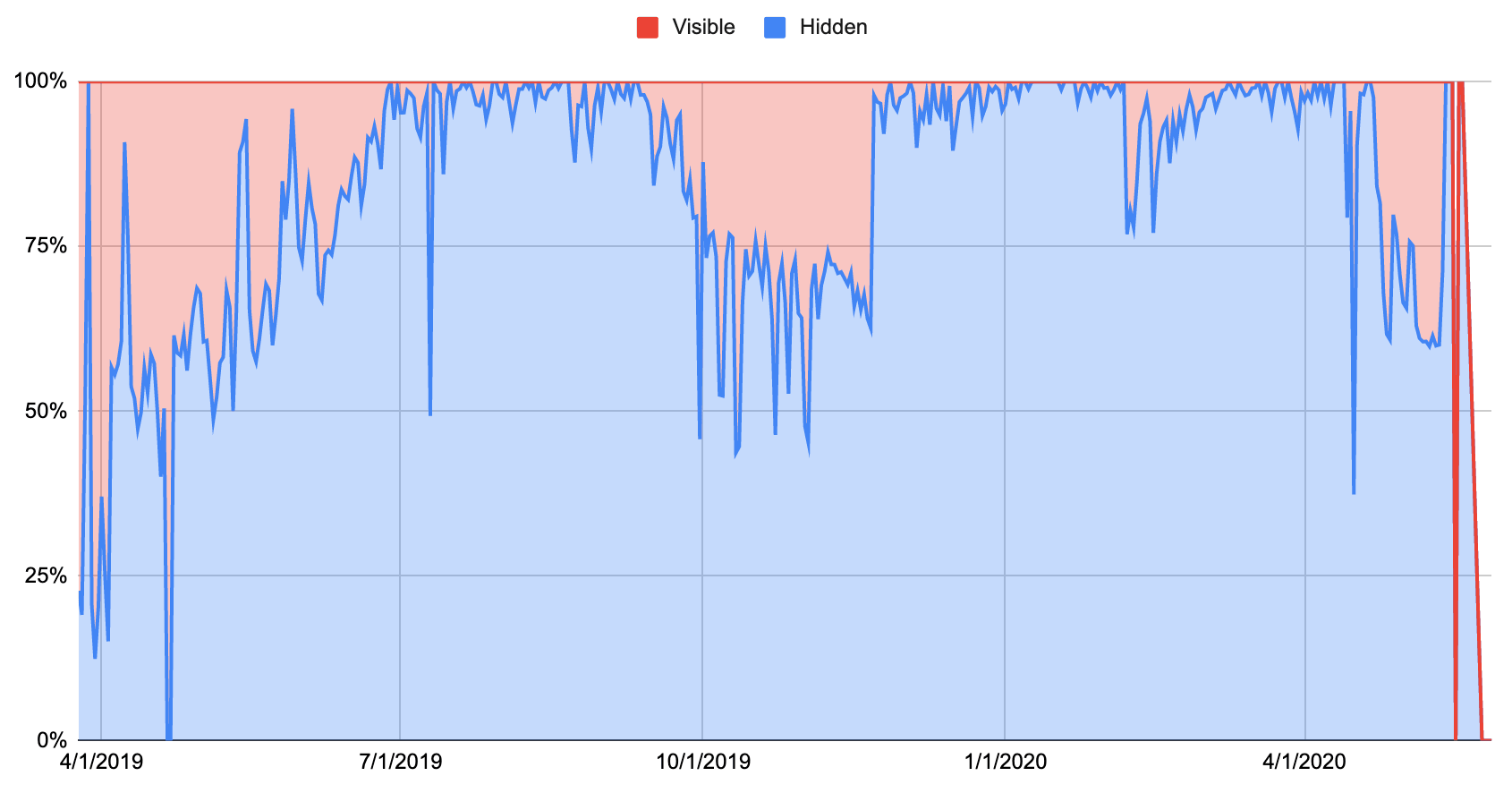

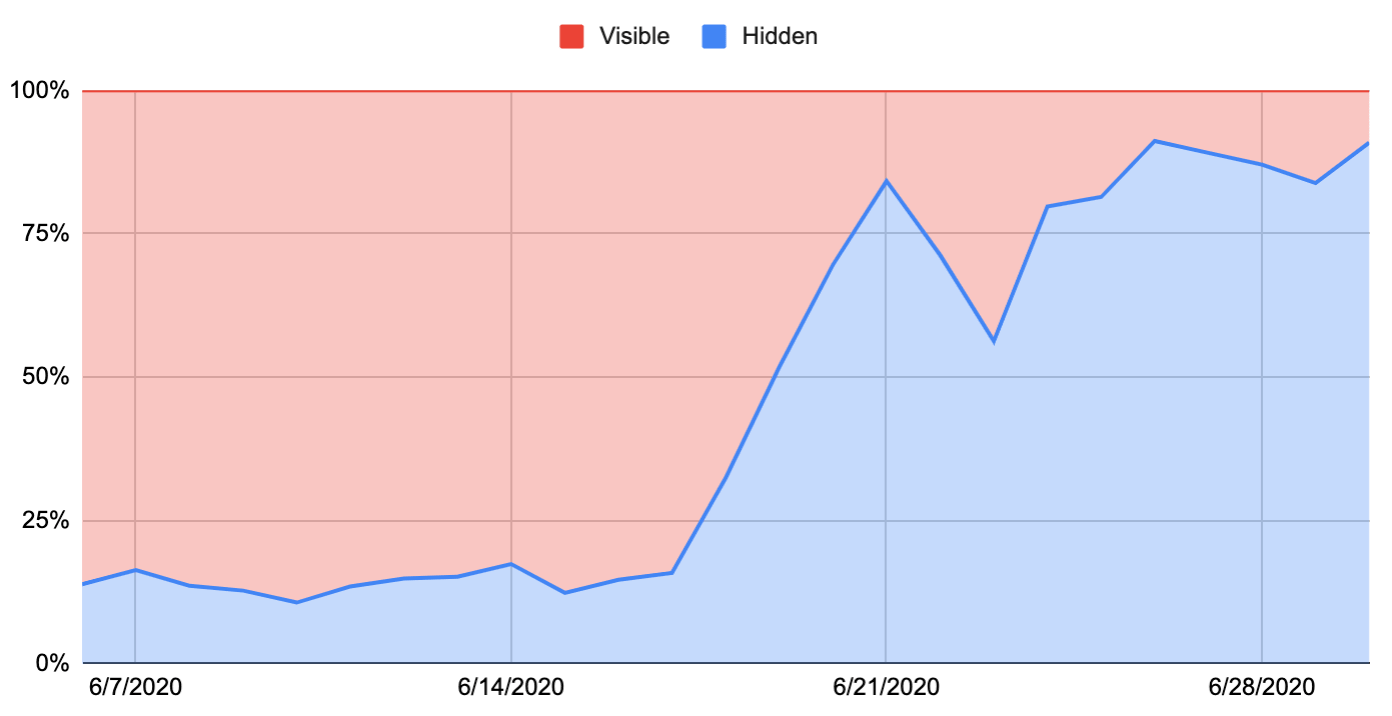

The reason the discovery of search terms plateaued is because the script constantly negated discovered search terms and added them to a probing campaign. As a result, the volume of ‘hidden’ search terms grew while that of ‘visible’ search terms dropped significantly. But what are these ‘hidden’ search terms? Apple only reveals search terms that have managed to reach at least 10 impressions. The search terms that are still low in volume will be ‘hidden’. As we notice in the examples below, as soon as the script starts to move the ‘visible’ search terms from discovery to a probing campaign while negating them in the discovery campaign, we get to a point where almost 70-90% of the search terms are not even ‘visible’ any more. In the last example, where we look at a shorter time frame, we can clearly see how the volume of ‘visible’ search terms drops from roughly 90% to almost 10% towards the end of the time period. One would assume that negating the ‘visible’ search terms would push the algorithm to continue digging for relevant search terms but that does not necessarily happen.

Are there ways in which this process can be revived and fed into to keep the engine running? Looking at how search match really works, a periodic metadata refreshment and creating a loop from ‘search match’ to ‘broad match’ comes to mind. We could also then turn off ‘search match’ all together, test previously found search terms through a probing campaign, and add them back as ‘broad match’ keywords until we have explored the entire set. As of now, we are investigating one of those ways –– adding the search terms back into a discovery broad match ad group after negating them –– to see if that sustains the volume and yields other variations of those search terms we might not have discovered yet. We will delve into the findings in a follow-up article, soon.

Finally, how do we know whether those search terms are valuable for us? How do they eventually end up performing when it comes to conversion volume and cost per conversion? In short, are they good-quality search terms?

As mentioned before, as soon as a new search term pops up in a discovery campaign, it is moved to a probing campaign where we can test its potential. So far, we have observed that, except for some search terms here and there, we have mostly uncovered relevant keywords worth keeping in the account. But while they definitely incur less spend once they are added to a probing campaign, the overall install and goal volume generated by those ‘hidden’ and ‘visible’ search terms in discovery campaigns tend to be much higher in comparison to the probing campaign. This is clearly because in a probing campaign we work with a limited number of keywords of which we would like to analyze the performance. This also limits the number of search terms we match to, and hence, get to a conversion volume that is lower than that of a discovery campaign. Nevertheless, this helps us make an informed decision as to which keywords we would like to include in our core campaigns.

In conclusion, discovery campaigns offer the advantage of scaling an account while also getting conversion volume. We have seen that, once they have been fully optimised, they contribute heavily to the overall goal (purchase, subscription, trial etc) volume. They also help in expansion to storefronts where you are unfamiliar with the language and do not have the resources to expand to right away. While the discovery function might plateau, you could keep them running just for the sake of traffic –– if the performance is acceptable, of course.

However, that comes at a price. In case of a tight budget and strict CPG goals, it is best to do your own keyword research thoroughly and perform periodic keyword expansion. However, if your goal is to optimize for performance, tread into this territory carefully by having a CPA goal in place. You could also just test it in one market and then expand to others. This way you can achieve more scale at an acceptable level. Finally, if keyword discovery is the goal, you would have to find ways to fuel the campaign before it loses its steam.