Editor’s note: This is a guest post from Shamanth Rao. Shamanth Rao is the founder and CEO of the boutique user acquisition firm RocketShip HQ and host of the Mobile User Acquisition Show podcast.

Retention, we know, is critical to an app or product’s long term financial health. Mathematically, the arguments are incontrovertible—including the fact that upstream retention metrics have a cascading effect.

We know, for instance, that a small retention win (even about ~5%) can result in a massive disproportionate improvement in LTVs.

That said, the standard manner of measuring retention (d1, d7 etc.) doesn’t capture the complete reality of how users are retained by your app. While it can tell you how many users returned one, seven, or even 30 days after they installed—highlighting the potential of your app to engage users long term—a big shortcoming of this paradigm is its inability to track how your app is engaging existing users or resurrected users.

The truth? DX retention doesn’t evaluate how your app engages existing users.

Consider the following example. Let’s say you run a sale on the fourth of July. What happens if your sale is a huge hit with your currently active users, who return in droves and engage more deeply than they did before—but your newly acquired users aren’t deep enough in the funnel to engage with it? Similarly, what happens when your sale brings back users who have previously lapsed?

Depending on when these users installed, you may see an increase in d21, d34 or d43 retention, which, given that it’s spread across very many cohorts, is not easy to spot and evaluate in a DX paradigm. Just as importantly, your d21, d34 or d43 retention doesn’t tell you if your app continues to be compelling to users after they return.

If your 4th of July sale brought them back, you should be asking if your app is going to continue to engage them after they’ve returned. Or will they take advantage of the sale, and never come back again? These are the essential questions that your DX retention number simply doesn’t do a good job of surfacing, simply because it is focused on how a cohort of new users progresses through their lifecycle, but does not directly reflect the health of existing or recurrent users.

Considering that the vast majority of users of most apps are existing users—and not new ones—this is a significant blind spot for the traditional DX retention numbers.

But what are the best ways to get the full picture? Below, I explore a few other metrics that fill the DX gap.

The solution for tracking current and resurrected uses

I found a set of metrics when I worked at Zynga that was a perfect solution to this problem. It was a very useful lens through which to look at your user base to get a more nuanced understanding of what is happening with your users.

It’s the trifecta of weekly retention metrics that we called CURR (Current user return rate), NURR (New user return rate), and RURR (Returning user return rate):

All three of these metrics help complete the picture painted by the DX retention numbers:

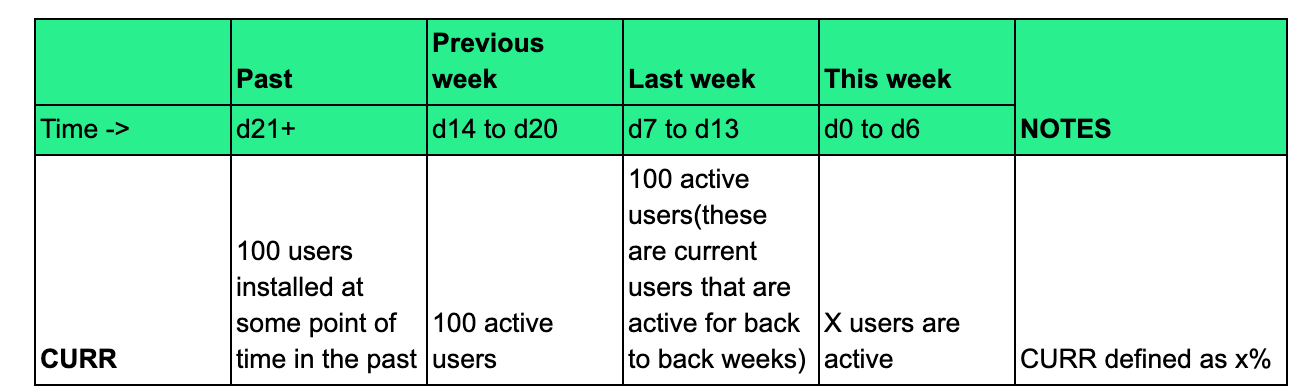

Let’s break it down a bit more. CURR—or the current user return rate—is defined as the percentage of “current users” that return during the current week.

A “current user” is defined as someone who installed at some point of time in the past—and has been active in the app for at least the previous two consecutive weeks.

So: if you had 100 “current users” (users who were active in each of the past 2 weeks), and x of them returned this week, perhaps because of a CRM campaign or an in-app sale, your CURR is said to be X%.

CURR is defined as the percentage of ‘currently active users’ who return during a week.

This shows how well your app is engaging your current users—or the most active users who are the lifeblood of your app. Did your new features engage these users better? Did a recent sale or communication turn them off?

CURR gives you the answers. Some of the more deeply engaging social games that I’ve seen have had a CURR of 80-90% and more.

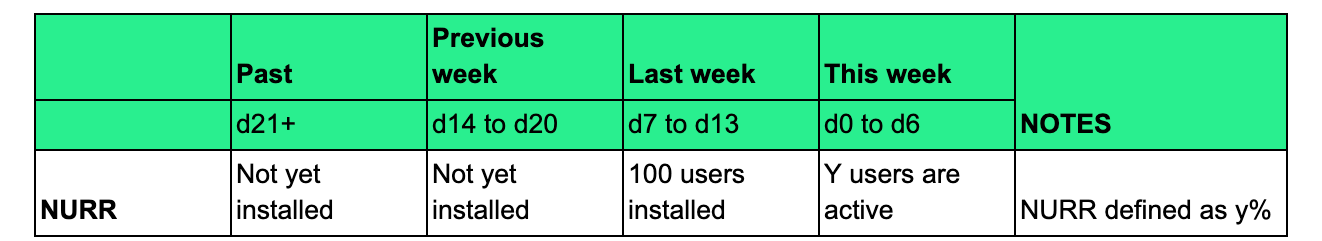

Next up is NURR. NURR—or new user return rate—is defined as the percentage of new users who have returned in any given week. These are users who installed an app for the first time in the previous week—and came back during the current week.

This is critical because, once a user has completed their onboarding and the early novelty of the app starts to wear off, it reflects what happens after a user is out of the d7 window. Is there enough content in the app to continue to keep these users back? And just as important: did your onboarding flow do a good enough job of educating users so they come back?

NURR gives you these answers. Some high LTV social games have had a NURR of 40-50%.

NURR is defined as the percentage of ‘newly acquired users’ who return during a week.

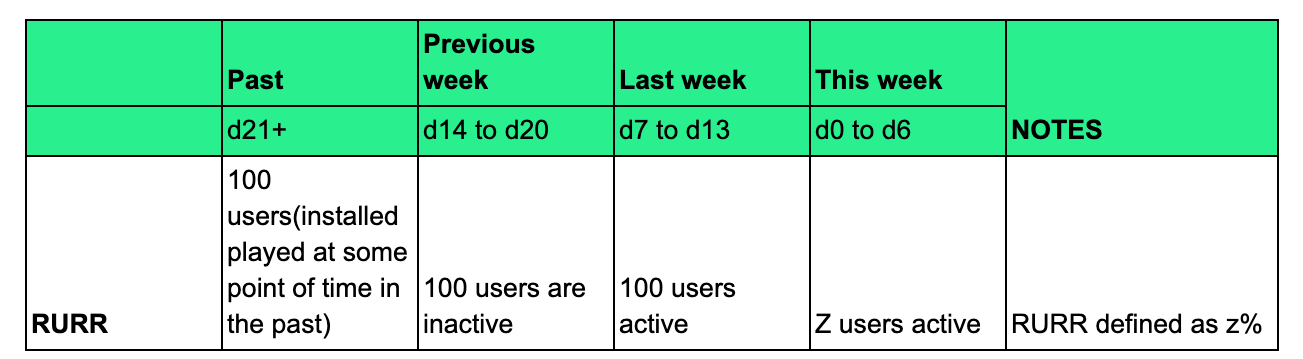

Lastly, we have RURR—or resurrected user return rate. RURR is defined as the percentage of resurrected users who returned in any given week. These are users who installed an app for the first time at some point of time in the past, went away for at least a week, and came back.

The important nuance here is that RURR doesn’t measure how well you resurrect users; it measures how well you retained those resurrected users. Getting users back via lifecycle communications is only the first step. What is just as critical is that your product be strong enough to retain these users when they come back. The strongest apps have a RURR of 45-50%.

RURR is defined as the percentage of ‘resurrected user return rate’ who return during a week.

What is critical, though, aren’t these metrics in and of themselves—but the fact that these are useful metrics to track on a weekly basis. Tracking how your NURR, CURR or RURR change over time can help monitor the health of your app in a more nuanced way than just the DX retention numbers can. You get to see not just how your new user cohorts retain over time—but also how your current users and resurrected users retain over the same period. It’s essential to understand DX alongside NURR, CURR and RURR for a full picture of your retention metrics.